Overcapacity, electrification, modulation… Three key takeaways from RTE’s 2025 Outlook

France must embark on a rapid electrification drive. Will this self-fulfilling prophecy from RTE come true? While the French transmission system operator (TSO) remains optimistic, it stresses the importance of launching the momentum as early as possible, as it presented its 2025 Outlook, updating projections for the power system out to 2035. RTE paints the picture of a France in a situation of electrical overcapacity and warns of the medium-term consequences of this configuration. A look back at the three key lessons to be drawn from this work, which will be published in full in the coming weeks.

1. Electrification must happen now

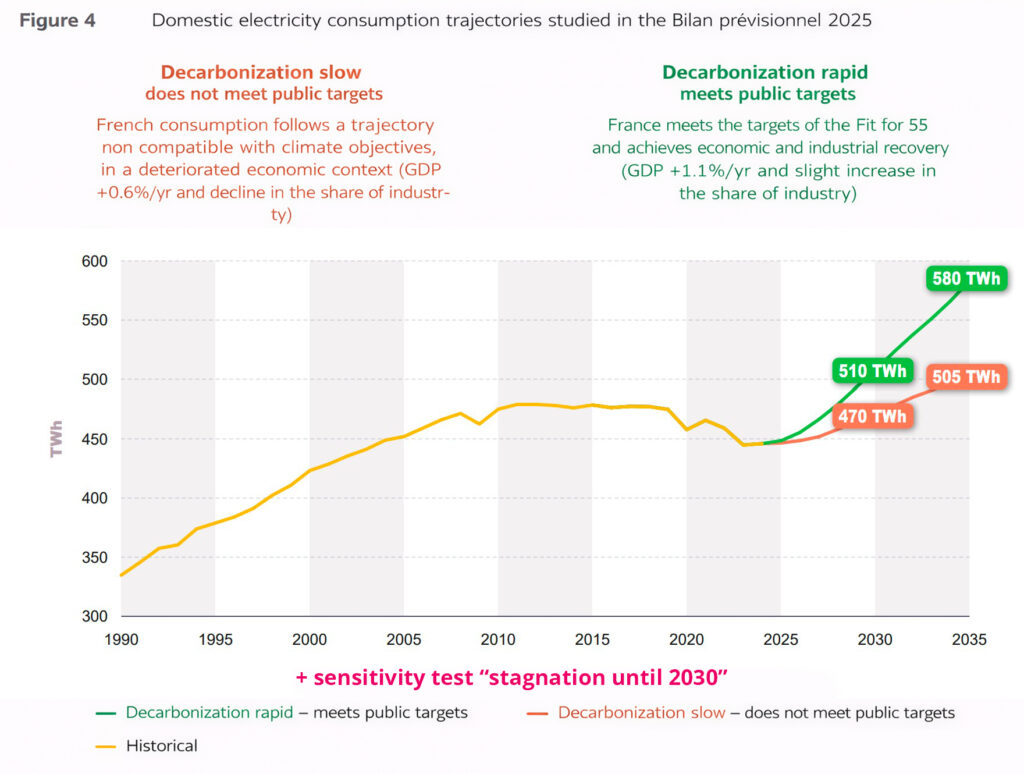

For the transmission system operator (TSO), the assessment of electrification of uses is mixed, weighed down by a drop in electricity consumption. Compared with the pathways presented in 2023, in the previous edition of RTE’s outlook to 2035, “exogenous impacts and shocks are placing us in the most degraded consumption scenario, that of constrained globalisation,” notes Xavier Piechaczyk, Chairman of the Executive Board of RTE. Meanwhile, generation capacities continue to grow, driven by the recovery of nuclear availability and the development of onshore renewable energies. This has led the TSO to reduce its electricity consumption forecast by 35 TWh for 2035 in its reference scenario, bringing it to 580 TWh. “Electrification remains relevant, with economic, environmental and sovereignty gains,” Xavier Piechaczyk reminds us.

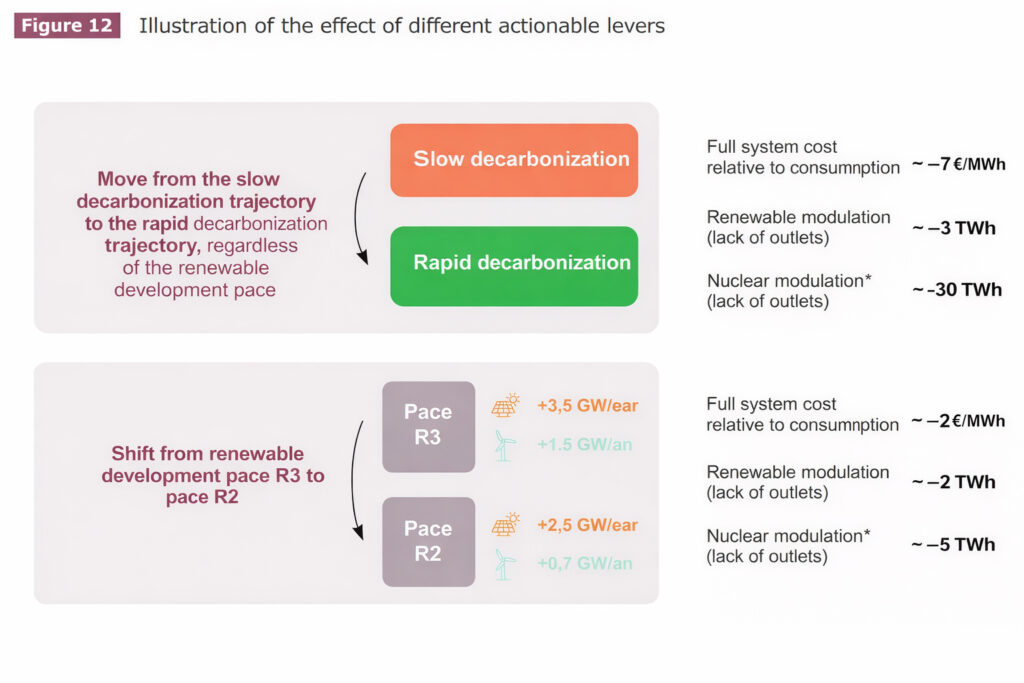

“Delivering electrification projects therefore remains a priority,” adds Thomas Veyrenc, Executive Director in charge of economics, strategy and finance. While the situation cannot be reversed before 2028 at the earliest, achieving electrification targets “will be decided in the coming quarters” if France is to remain on a so-called “rapid decarbonisation” trajectory. Without renewed momentum, “it will be necessary to temporarily regulate the pace of development of onshore renewable energies,” notes Xavier Piechaczyk. This regulation must be applied sparingly and should, as far as possible, spare offshore wind, whose production is located in France. “Any slowdown in the deployment of renewables must be proportional so as not to jeopardise supply chains that are currently being relocated and that we will need after 2035,” adds the Chairman of RTE’s Executive Board. Nevertheless, promoting electrification rather than regulating renewables deployment remains “three times more economically efficient,” Thomas Veyrenc insists.

2. Optimal conditions for decarbonisation

Electricity production in 2024 reached 539 TWh, its highest level in five years, compared with national consumption of 449.2 TWh. This is not France’s first episode of overcapacity: since the mid-1980s, the expansion of the nuclear fleet outpaced consumption growth, leading to a record export balance of 76 TWh in 2002. “Structurally, overcapacity is not a problem, as it brings resilience and competitive prices,” notes Xavier Piechaczyk. “At least as long as it does not result in over-equipment.”

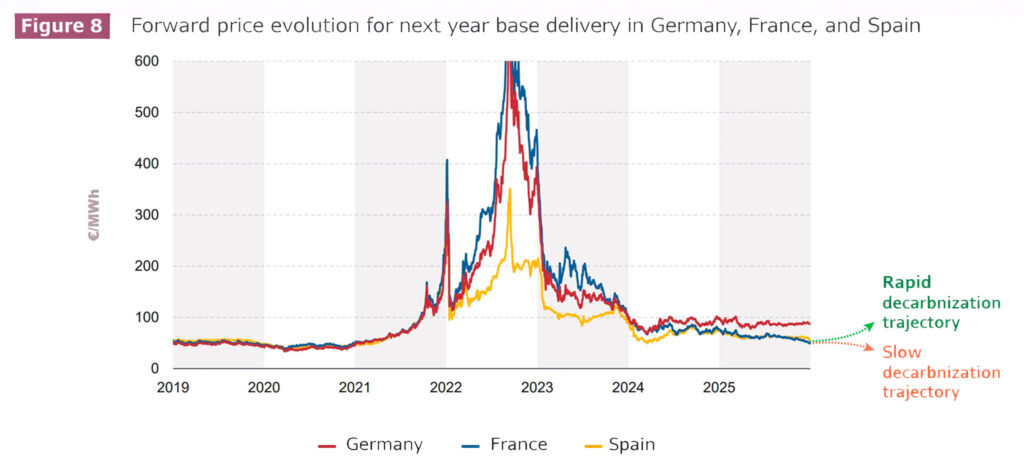

The first positive point is export capacity. After severe unavailability in 2022, 2024 was marked by a record level of electricity exports, reaching 89 TWh. This resulted in a net total export value of €5 billion. This trend is continuing in 2025, with the annual balance (not yet final) already reaching 82 TWh as of November 31. A new record is not out of the question. Domestically, abundance leads to lower costs. France’s overcapacity allows wholesale prices to remain highly competitive, hovering around €50/MWh for delivery next year. French prices remain lower than those of neighbouring countries, with a decoupling from German and Spanish prices. The gap with Germany is around €30/MWh. The Sfen had already highlighted the competitiveness of French electricity in its “nuclear in figures” feature.

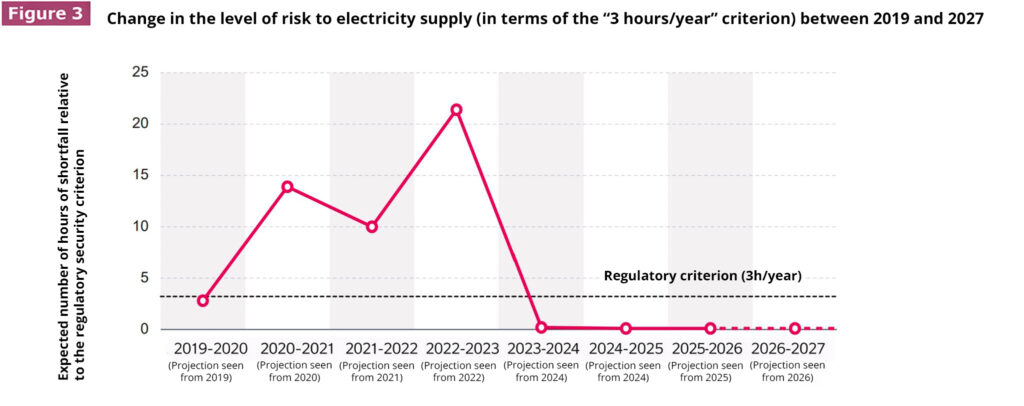

These factors provide ideal conditions for electrification. RTE stresses that “there is no risk of competition between uses across the different sectors that must be prioritised for climate action.” France could simultaneously develop electricity-intensive sectors, such as the production of synthetic fuels for aviation and maritime transport, which would require around 20 TWh to replace 5% of fossil fuels. Data centres could also expand without creating supply conflicts, despite estimated needs of between 6 and 10 TWh per year by 2030. In the shorter term, overcapacity also offers “historically low risk levels for getting through winter periods or dealing with disruptions to generation assets,” according to Thomas Veyrenc.

3. Economic losses and technical constraints to avoid

While overcapacity brings advantages, it also entails medium- and long-term technical and economic downsides, unless countermeasures are implemented. Missing the electrification turning point would mean forgoing part of the climate and strategic benefits expected by 2035. If targets are met, RTE forecasts a decline in fossil energy consumption from 60% to 30–35%, offset by a rise in electricity’s share, from 26% in 2024 to between 40% and 45% in 2035. “This reduction of around 500 TWh in fossil energy consumption compared with 2024 would represent a major trade advantage,” stresses Xavier Piechaczyk. By way of reminder, fossil fuel imports represented €64 billion of expenditure in France in 2024.

From an economic standpoint, electricity exports could also become problematic. “Overcapacity is not an issue as long as surplus production can be exported; otherwise, the system becomes over-equipped,” recalls Thomas Veyrenc. According to RTE’s projections in a degraded scenario, the export balance would stabilise between 80 and 110 TWh due to limited economic outlets in Europe. The nuclear fleet would be increasingly called upon to modulate output, with around 50 TWh, compared with 30 to 40 TWh in an optimised scenario. “Without increased electrification, the nuclear fleet will be required to modulate more, because decisions are driven by market price signals,” Thomas Veyrenc points out. Regulatory measures could therefore be a way to limit nuclear modulation. This issue remains to be followed closely, as EDF is expected to publish a report on the subject soon. Finally, the volume of curtailed renewable energy would be multiplied by two or three, reaching 30 GW by 2035, compared with around 10 GW in 2025. In this context, consumption and production trajectories in neighbouring countries will influence export capacity.

From an internal system perspective, fixed costs are spread over the volume of electricity consumed. If consumption is lower than expected, the cost per unit of electricity rises. By 2030, this overcapacity would translate into higher system costs. On average, the cost of the electricity system in euros per megawatt-hour would be 7% higher depending on whether a rapid or slow decarbonisation scenario is considered. In the event of stagnant consumption, this additional cost could reach 10%. ■

By Floriane Jacq and Simon Philippe (Sfen)

Image: Jeff Pachoud / AFP

Charts taken from RTE’s 2025 Outlook