Universal Nuclear Levy (VNU): four questions to understand the mechanism replacing ARENH

The Universal Nuclear Levy (Versement nucléaire universel – VNU) will replace the Regulated Access to Historic Nuclear Electricity (ARENH) as of 1 January 2026. This new mechanism, enshrined in the 2025 Finance Act, modernises the way nuclear electricity production is valued and how its revenues are shared with French consumers. Here are the key points to understand.

1 — Why is ARENH coming to an end?

ARENH was introduced in 2011 to allow alternative electricity suppliers to purchase a share of EDF’s historic nuclear production at a regulated price (€42/MWh) in order to foster competition. After 15 years, this mechanism comes to an end on 31 December 2025, as предусмотрed by the Initial Finance Act for 2025.

The context has evolved: market prices now better reflect actual production costs, and economic stakeholders consider that the conditions for effective regulation have changed. Replacing ARENH was planned from the outset, and the VNU is part of this transition towards a more dynamic energy framework. It also allows for fairer remuneration for EDF and the nuclear fleet.

2 — What was the main issue with ARENH?

From the perspective of EDF and many actors in the nuclear sector, ARENH was never merely a competition tool. Over time, it became a large-scale value transfer mechanism to the detriment of the French public producer. In its report on “EDF’s economic model”, published in September 2025, the French Court of Auditors (Cour des comptes) calculated that in 2022, “over the period 2011–2020, ARENH represented a loss of revenue of €5.3 billion for EDF compared with a situation without specific regulation of nuclear electricity prices, while maintaining regulated retail tariffs at a level reflecting EDF’s accounting production costs.” The Court also found that ARENH no longer made it possible to cover the full production costs of the nuclear fleet. These costs gradually reached and then exceeded, from 2019 onwards, the €42/MWh threshold.

As a result, EDF bore all the risks and investments: construction, lifetime extensions, safety upgrades, waste management, and more. Yet the company benefited little or not at all from rising electricity prices. Under ARENH, up to 100 TWh of nuclear production had to be sold at €42/MWh regardless of market prices. When prices were low, alternative suppliers did not purchase ARENH volumes; when prices surged, they exercised their right at €42/MWh. EDF was therefore exposed to downside risks while being deprived of upside gains. By contrast, competitors benefited from a free option on French nuclear production, without contributing to securing the balance of the power system.

3 — How does the VNU work?

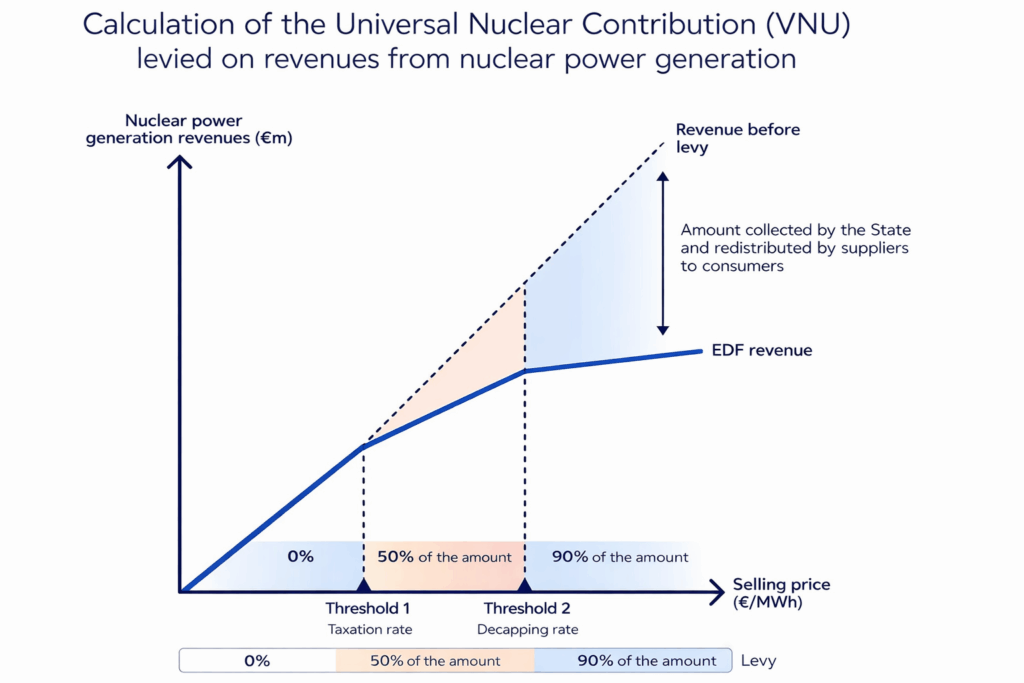

The Universal Nuclear Levy (VNU) is based on a different principle: it no longer sets an administered price, but instead redistributes part of the revenues from nuclear electricity sales to consumers when certain price thresholds are exceeded. In September 2025, the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) estimated the full production cost of the historic nuclear fleet (including operation, maintenance, depreciation and waste management) over the 2026–2028 period. This cost, set at €60.3 (2026€/MWh) for 2026–2028 and €63.4 (2026€/MWh) for 2029–2030, as analysed by Revue Générale Nucléaire, serves as the technical reference for defining the VNU taxation thresholds. The CRE has also published its estimate of EDF’s unit revenues from nuclear power at €60.94/MWh in 2027, corresponding to total revenues of €21.94 billion for a target production of 360 TWh.

EDF now sells the vast majority of its nuclear output at market prices, without a fixed quota, but subject to revenue redistribution thresholds:

-

Below a first threshold, EDF retains all its revenues. It should be noted that since the end of the 2022–2023 gas crisis, forward electricity prices have generally ranged between €60 and €70/MWh.

-

Above a first “taxation” threshold, set at €78/MWh in a draft decree, 50% of the excess revenues are levied by the State and redistributed to all consumers via a dedicated line on their electricity bill.

-

Above a second “capping” threshold, set at €110/MWh in a draft decree, the redistributed share may reach up to 90% of the excess revenues.

4 — What are the benefits of the VNU for nuclear power?

Above all, the VNU marks the end of a system that captured part of the value of nuclear power without bearing its costs. It is seen as a reconnection between production, industrial risk and revenues, a model more compatible with the long-term investment profile characteristic of nuclear energy. The VNU removes privileged access to low-priced nuclear electricity for alternative suppliers. They will now either have to buy electricity at market prices or invest directly in generation capacity. For EDF and the nuclear sector, this represents a return to competition based on investment and innovation, rather than regulatory arbitrage.

It should be noted, however, that EDF opened Nuclear Production Allocation Contracts (Contrats d’allocation de production nucléaire – CAPN) in November 2025 to suppliers authorised to purchase electricity for resale to final consumers, as well as to electricity producers. These contracts allow beneficiaries to access a share of the actual output of the nuclear fleet at prices close to production costs, in exchange for risk sharing. At present, EDF is making 1,800 MW available under this mechanism, corresponding to approximately 10.6 TWh per year from 2027 onwards. This scheme has been open to energy-intensive French industries since 2023.

Finally, the VNU also aims to protect consumers against market price increases, as the proceeds from the levy will be returned to consumers through reductions in their electricity bills. ■